This was first published on the Cabinet Office website. Well, we did it! We delivered GOV.UK. It was big and hairy and we did it by being agile. The benefits are clear:

- We were more productive: By focussing on delivering small chunks of working product in short time-boxes (typically 1 week development sprints) we always had visible deadlines and a view of actual progress. This is powerful stuff to motivate a team.

- We created a better quality product: We used test driven development; browser and accessibility testing were baked into each sprint and we had dozens of ways of testing with real people as we went along to inform the design and functionality of the product.

- We were faster: By continually delivering we were able to show real users and our stakeholders working code very early on and get their feedback. What you see now on GOV.UK was there in February, albeit in a less fully featured and polished way. Lifting the lid on it did not seem like a big reveal; it felt like an orderly transition.

These characteristics are true of all our projects, but I wanted to talk about agile at scale with 140 people and 14 teams and what I've learnt. In so far as I know this is a relatively new area and there is not a consensus view of how to do it.

Be agile with agile

The foundation of this success was people that were agile with agile. Props to people like Richard Pope who helped set the tone of our culture at GDS, which is one where people are open to learning, improving and workspace hacks without the dogma of big 'A' agile. It’s all about that. If you don’t have this embedded in your teams then what I write below doesn’t matter.

Lesson: a working culture that values its people and embraces experimentation is essential to success.

Growing fast is hard

We grew from a cross-functional team of 12 for the Alpha version of GOV.UK, to a programme of work involving 140 people over 14 teams. There was a period from April to June where we grew 300% in three months, which was crazy but felt necessary due to the scope of work.

Our expansion was organic and less controlled than our original plans had suggested. Had we focussed on fewer things from the outset, the overhead of getting people up to speed and the additional communication needed to manage this would have been far less and our momentum would have increased.

Lesson: We should have committed to doing less like the books, blog posts and experts say.

Don’t mess with agile team structures

Clearly defined roles within teams as Meri has said are vitally important. Our teams emerged rather than beginning the project formed with the core roles in place. The consequence of this compromise was a blurring of roles which meant that certain people took on too much. In these teams people faced huge obstacles around communication, skills gaps, confused prioritisation and decision making and ultimately productivity suffered.

Lesson: This experience reinforced the importance of agile team structures. Don’t mess. The team is the unit of delivery!

Stand-ups work for programmes

When you have a team of 10 people conversations can happen across a desk or during stand ups. As we expanded rapidly communication became increasingly strained. There were fewer opportunities for ad-hoc conversation and talking between teams was harder. We solved this with a programme level ‘stand-up of stand-ups’ attended by delivery managers from each team.

We had up to 14 people and we nearly always managed to run it within 15 mins. We held ours twice a week which gave us good visibility and opportunities to help each other. People willingly came along, which I take as a good sign the meeting was valuable.

Lesson: In the future we’ll probably split this into another level of stand-ups so we have one for teams, one for working groups of teams (or sub-programmes) and one for cross-GDS programmes.

Monitor with verifiable data

We organised the programme into working groups which had one or more teams. Most teams used a scrum methodology and split their work into releases (or milestones), epics and user stories.

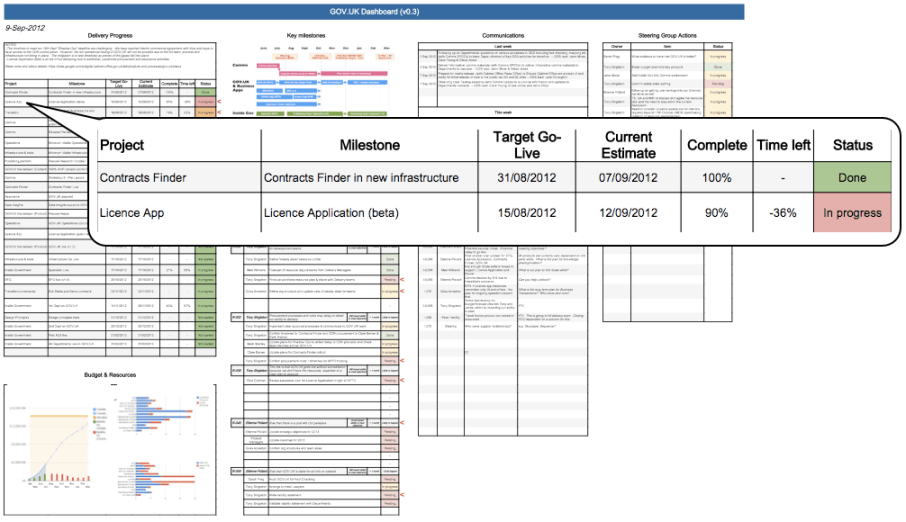

By tracking these we generated verifiable data about progress, scope completeness and forecasts of delivery dates. By aggregating this data we created a programme dashboard for teams and senior management.

The image above shows the GOV.UK programme dashboard. This view of the programme was created using data generated by the teams doing their day-to-day work using tools like Pivotal Tracker and was not based on subjective reporting by a project or programme manager. The callout shows two milestones for two different teams. One was completed, the other is shown to be 90% complete with an estimated delivery date a month later than our target date. This was verifiable data based on the number of stories and points left to deliver the milestone with historical data on a team’s speed to build, test and deploy the remaining scope.

This was the bit that made me most happy and made tracking and managing the programme much, much easier than gantts.

Lesson: Use independently verifiable data from your agile teams to track your programme

Use Kanban to manage your portfolio

We used a system of coloured index cards to map out the components of the programme. This captured key milestones, major release points and feature epics and because it was visible, it encouraged shared ownership of the plan and adaptive planning throughout the delivery.

We gathered Product Managers, Delivery Managers, the Head of Design and the Head of User Testing around this wall every two weeks to manage our portfolio of projects and products. The process forced us to flag dependencies, show blockers and compromises.

Lesson: This approach was successful up to a point but in hindsight I wish we had adopted a Kanban system across the programme from the outset. It would have provided additional mechanisms for tracking dependencies, limited work in progress and increase focus on throughput. I would also formalise a Portfolio Management team to help manage this.

Everything you’ve learnt as a project or programme manager is still useful

When I started using agile, someone said me, “when things get tough and you want to go back to old ways, go more agile, not less”. This has stuck in my mind.

When I was designing the shape of the programme and working out how we would run things I wanted to embed agile culture and techniques at its heart. For example, we used a plain English week note format to share what happened, what was blocking us sprint to sprint rather than a traditional Word or Excel status report.

In tech we always say we’ll use the right tool for the job and in programme management the same is true. In the same vein I opted to use a gantt chart as a way of translating milestones and timings to stakeholders but internally we never referred to it and were not slaves to it.

Risk and issue management is an important aspect of any programme. The usual agile approach of managing risks on walls scaled less well into the programme. Typically in smaller teams you might write risks, issues and blockers on a wall and have collective responsibility for managing them. We scaled this approach to our stand up of stand ups and this worked well for the participants: it was visible, part of our day to day process, we could point at them and plan around mitigation.

But there was a moment when the management team asked for a list of risks and issues and pointing them at a wall was not the best answer so we set up a weekly risks and issues meeting (aka the RAIDs shelter) and recorded them digitally. This forum discussed which risks, issues, assumptions and dependencies were escalated. By the book it fits least well with the agile meeting rhythm but it gave us a focal point to discuss concerns, plan mitigation and fostered a blitz spirit.

We have some way to go to make it perfect but we have learned that within GDS agile can work at scale. We’ve embraced it culturally and organisationally and we’ve learnt an awful lot on the journey. Some of the lessons we've learnt have already been incorporated into how we’re working now and I look forward to sharing more about this in the future.