Designing and operating modern, internet-era services is different from what you might be used to, but it’s not rocket science. It’s the application of a few simple principles, a simple flow of work and some tweaked behaviours. If you’re a leader thinking of doing service design for the first time, these are some of the things you can do to increase your chances of success.

Empower teams by giving them problems to solve

Resist the temptation to jump to guessed solutions. It’s important to openly acknowledge that understanding the problems to solve, especially those of the user, is the place to start. By better understanding challenges, opportunities and the needs of users you increase the chances of delivering the right thing.

Set up a small, 100% dedicated, cross-disciplinary team with the relevant expertise to explore a problem space for 3-5 weeks. Direct their efforts on an area of opportunity that has potential to deliver on your strategy, but where the edges are unclear.

Investing in discovery activities like this saves wasted effort later on and creates the beginnings of an inspired, empowered team, committed to solving a problem with a habit for learning.

Test your riskiest assumptions by building working prototypes

Explore the art of the possible by building a working prototype (an ‘alpha’) and testing it with potential users. It is a quick and effective way to test your riskiest assumptions and better understand the needs of the user. The value of learning is in reducing the risk of prematurely committing resources to delivering the wrong thing or making incorrect assumptions that prove costly.

Don’t build an app, build a team

Empower a team to meet the needs of the user. Make sure they can do this free from the imposition of political constraints to avoid building a product or service that suboptimally reflects the shape or behaviours of the current organisation.

Trust the team to own their process and choose the tools they wish to work with. Support them to shape their working environment in ways they want. There is no simpler, more powerful way for a leader to signal empowerment than by allowing a team to break some long-standing but innocuous rules.

During an alpha it is important the team can demonstrate they work well together and that they’ve understood and sufficiently explored complex areas of the service (e.g. security, legal, identity) – not just a shiny new interface.

Embed the change where you want to see it happen

An essential measure of success is landing new ways of working into the organisation. You can vastly increase the chances of that happening by co-locating a 100% dedicated, cross-disciplinary team where you want to see the change happen.

By the end of an alpha, the team will need to generate sufficient political momentum to surmount the internal barriers to the service going live (usually as ‘beta’).

Quickly put a real service live in front of real users

Everyone should expect the ‘beta’ service to be put in front of users quickly – say within a month or so. It won’t be complete but it will be the beginning, a thin slice, of a real service with real users. For organisations not used to working this way this is an important psychological hurdle to overcome, and a condition for success for delivering modern, internet-era services.

Deliver incrementally and iteratively

Ensure the approach to delivering the service remains incremental and iterative, driven by desired outcomes rather than a fixed plan. Allow the team to experiment with both the service design and how the service is operated.

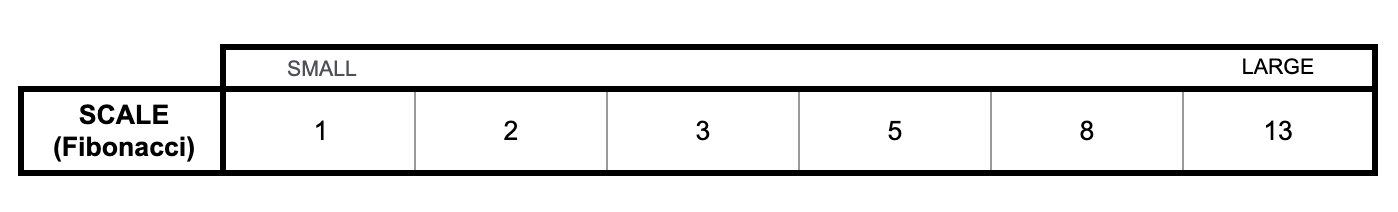

It doesn’t matter how big or complex the imagined future service is, break it down into smaller parts and build in short, timely feedback loops. Learning this habit and way of working will help you build a service that better meets the needs of end users and front line workers who provide the service.

Start small and grow organically

Sponsors should understand it’s better to start small and grow organically. The organisation must resist the temptation to impose programme structure on a beta team, or believe that by adding more people, workstreams or management layers it will deliver faster – it won’t.

Over engineered programme-level hierarchies or overbearing governance produce noise; noise slows down self-organising, motivated teams. Your role as a leader should be to support the team to figure this out as they go.

Commit to challenging the status quo

Provide the top cover, including committing day-to-day leadership from within the organisation – someone who is trusted and capable of navigating and challenging the status quo.

In fact, it should be understood that the beta will be outside the norms of programme management and governance. Part of the beta will be to explore how both need to adapt.

Go and see delivery for yourself

You’ll know this approach is working and whether you’ve nurtured a good team if they can demonstrate they can regularly deploy and iterate the service based on real user feedback.

Encourage all stakeholders to commit to going to see what and how the team is delivering and to listen to how users are responding. They will see the service coming to life and continuously improving week by week.

This is a far more effective way of assessing true progress and providing timely challenge than by reading and responding to an emailed report sent from afar. Get out of the meeting room and go to see delivery for yourself.